11/6/17 Decision deadline for 59,550 Hondurans and Nicaraguans: 6 DAYS

11/23/17 Decision deadline for 50,000 Haitians: 23 DAYS

01/08/18 Decision deadline for 195,000 Salvadorans: 69 DAYS

In a piece for La Opinion, Pilar Marrero provides a comprehensive situational breakdown and much-needed look at the 300,000 Salvadoran, Honduran, Nicaraguan, and Haitian adults now incredibly vulnerable to deportation due to the Trump Administration’s potential elimination of Temporary Protected Status (TPS).

The article in its entirety can be accessed here and an English translation follows below:

Who are the ‘Tepesianos’? Over the next three months, the Trump Administration could eliminate an immigration status that has protected Salvadorans, Hondurans, Nicaraguans and Haitians. These are some of the people who will be affected.

First it was announced that DACA– a program protecting more than 800,000 young DREAMers whose stories are popular and well-known around the country– would be rescinded. Now the same fate could affect TPS.

The conclusion many activists have reached is if Donald Trump didn’t have the heart to save DACA, what will he do with about the 300,000 Salvadoran, Honduran, Nicaraguan, and Haitian adults that most Americans do not know about?

Over the next two months, the time will come for a decision on the situation of these communities who have lived with a temporary immigration status for years.

TPS is a temporary program that protects people from specific countries from deportation and provides them with work permits. Generally, these are people from countries that have suffered a natural disaster, war or civil conflict.

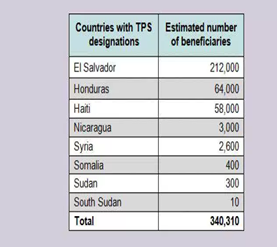

The following table shows which countries have TPS and how many people from each country are protected by the program:

The program was first launched in 1990, and currently eight countries have TPS, but after Donald Trump’s Administration rescinded DACA for young DREAMers andannounced a mere 6-month extension for Haitians with TPS in May, the fear is that it do the same with the rest of the TPS beneficiaries.

November 6 is the deadline for a decision on TPS that will affect 59,550 Hondurans and Nicaraguans; November 23 for 50,000 Haitians; and January 8for almost 200,000 Salvadorans.

Who are the “Tepesianos”?

About one in four of the 206,000 TPS beneficiaries from these three countries came to the United States when they were under 16 and more than half of Salvadorans and Hondurans have been in this country for more than 20 years.

At least half of Salvadorans, Haitians and Hondurans with Temporary Protection Status (TPS) living in the United States are homeowners and almost 100,000 mortgages would be up in the air if the Donald Trump Administration decides not to renew their legal status.

Their participation in the workforce is higher than the average American and also of the average foreign-born worker. Between 81 and 88% are working in, and a part of, the most important industries in the country, added the report publishedThursday. About 27,000 are business owners and job creators.

It is estimated that at least 50,000 work in construction, 32,000 in the food industry, 16,000 in landscaping, 10,000 in childcare and 9,000 in the grocery industry.

Salvadorans, Hondurans and Haitians have also become the parents to 273,200 U.S.-born children.

The states of the country with the largest TPS populations are California, 55,000; Texas, 45,000; Florida, 45,000; New York, 26,000; Virginia, 24,000; and Maryland, 23,000.

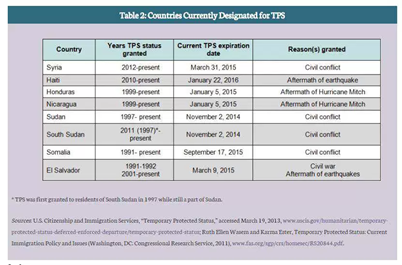

This USCIS chart contains figures and information regarding the current TPS country recipients, when they were granted, when they expire and the reasons granted.

Iris, from Honduras: 25 years in the U.S.

Iris Acosta has lived all kinds of experiences since arriving in the United States in 1992 from Tegucigalpa, Honduras.

One of her first jobs was as a nanny and live-in maid for a Los Angeles family. Her employers made her sleep in the garage on a mat after the children gave her chicken pox.

“There they put me, next to the car, for my fever to pass,” recalls Iris. “I was paid $95 a week to work from Monday to Saturday from 6 am until I put the kids to bed.”

During those years she was undocumented, but in 1999 she took advantage of the Temporary Protection Status or TPS offered by the U.S. government to Honduran and Nicaraguan citizens in the wake of the devastation caused by Hurricane Mitch, the most damaging hurricane to hit the Western Hemisphere since 1780.

After the hurricane, 7,000 people died and 12,000 were injured. Additionally, 35,000 homes were lost and virtually all economic sectors within the country were paralyzed.

After the TPS, Iris has had two long-term jobs, one at Children’s Hospital and one at the W Hotel in Westwood, where she still remains employed as a maid. “I do not like to change jobs frequently,” she said. “Especially when it offers good health insurance, which helped me when I had cancer a few years ago.”

His two sons stayed in El Salvador and she raised them from afar. One is a stylist and the other is studying to become a psychologist. She was in the process of buying a two-bedroom house when the real estate agent discovered that she was a TPS beneficiary.

“He told me to wait until January, which is when the permit expires,” she said. “That’s really brought me down because we do not know if the government will renew our status”.

At age 51 and having lived in the U.S. since she was 27, Iris does not see a future in Honduras, especially since this country is considered the most violent in the Western Hemisphere.

“I only went to Honduras once in 2008 when my mom had a heart attack,” Iris said. “I’ve never asked the government for anything. I’ve paid my taxes, but in Honduras there is no future for me.”

The Trump Administration must make a decision by November whether or not to extend this benefit to Hondurans and Nicaraguans.

Yesenia, from El Salvador: 17 years in the U.S.

Yesenia Reyes was 22 years old when she came undocumented to the United States,leaving her two little girls behind who had asked to bring back two dolls that could dance and sing. It was hard to leave, but the alternative was to continue to suffer domestic violence and constant sexual harassment.

When she arrived, immigration took her in, and she felt protected.

“For me, being locked up here was better than being there,” she recalled.

Upon leaving the detention center, she sought for work to survive. However, sexual harassment also became an issue here.

“I looked for a job in a dry cleaner, but since I did not have any papers the owner told me after some time that to keep the job I had to get him,” she said.

In 2001, Yesenia qualified for TPS. It was the second Temporary Status of Protection granted to that country and was designated by George W. Bush in 2001 after three earthquakes that displaced to 1.3 million people and caused more than 1,000 deaths.

There are more than 212,000 Salvadorans with TPS, the largest group benefiting from this type of program.

TPS gave Yesenia economic stability.

“I left that job and found work in a hotel, where I was almost ten years,” Yesenia said. “In fact, most of the time I’ve held two jobs and have four citizen children with my current partner.”

Three girls and one boy were born here– between ages 15, 14, 9 and 4– plus her two older girls that she sent for as soon as possible.

“El Salvador is very beautiful but there is a lot of gang activity and there are no labor protections,” said Yesenia, who recounted an experience working in a pupusería.

“When I asked what time the employees ate, they told me there was no time, we only ate leftovers from the dishes,” she said.

Losing TPS and having to return with their children would be “sending us to the slaughterhouse.”

Myrtha, from Haiti: 7 years in the U.S.

Destiny wanted Myrtha to leave Haiti for the United States a day before a devastating earthquake struck the island on January 12, 2010 killing tens of thousands and leaving 1.5 million homeless. The girl was 23 years old and accepted TPS when the U.S. government offered the benefit a few days later.

About 58,000 Haitians remain protected by the program, but the U.S. government gave them a six-month extension in May to prepare to return to their country .A final decision is expected in November.

Upon arriving in the U.S., Myrtha gave birth to her daughter, who is now in third grade. With what she earns from her job, she helps her parents in Haiti.

“Nothing has been rebuilt in Haiti since the earthquake and my parents have no home. Here my daughter studies, I drive, and everything is fine, ” she said. “I work in a unionized hotel and I have stability. In Haiti on the other hand, you have to pay for everything, even for school.”

When she thinks of returning to Haiti, Myrtha feels pain “in my body and in my spirit”.

“I have no plans, only to fight that they allow us to stay. I hope Mr. Trump has heart for us because we work hard,” she said.

María Ponce, El Salvador: 27 years in the U.S.

The story of Maria is like many other Salvadorans. She came here in 1990 escaping for the civil war. She gained TPS after the earthquake because she was afraid to ask for the first TPS offered during the war. She worked hard, had three children born in the United States in addition a son who was in El Salvador.

She lives in Boyle Heights, is a health promoter and before that, she worked 10 years at a store.

However, not all has been easy. Her mother was murdered at the hands of gangs in the San Salvador neighborhood her the family lived had lived many years in.

It was only five years ago and still, it is hard for her to talk about.

“With the little money my sister and I sent, my mother had a small restaurant where she used to serve food,” she said. “The mara (gang) asked for a fee, as they ask of everyone. One day they waited for her to go out with my brother, and when she was almost home they robbed her, took the money and shot both of them.”

One shot hit his mother’s neck. The other perforated her brother’s lung who still suffers from the aftermath.

“She died on March 8, 2012, the same day as International Women’s Day,” she said in a broken voice.

Violence in El Salvador says it all.

“My three children born here are in college, they are forging a future for themselves. I want to be here to continue being able to live.”